I was planning on going to the Olympic Games in Tokyo this year. My family and I had tickets reserved, a place to stay, but mostly we wanted to see sports. We would cheer for the Puerto Rican team, all while supporting athletes bringing pride to their nations.

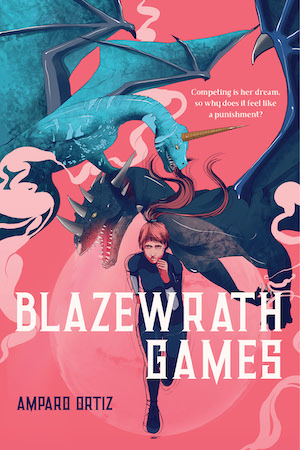

Obviously, that’s not happening anymore. Instead, I gravitated towards Blazewrath Games, Amparo Ortiz’s debut young adult novel about a Puerto Rican girl participating in the dangerous fictional sport called Blazewrath, an event involving dragons, riders, and magic, and athleticism.

Ortiz’s fantasy novel melds the lore and worldbuilding (and dragons) of How to Train Your Dragon with the stakes, team dynamics, and intrigue of Marie Lu’s Warcross. In Blazewrath Games, Lana Torres, wishes to become a part of Puerto Rico’s first National Blazewrath Team and thus compete at the World Cup. The Blazewrath team is composed of multiple members, but the position that Lana wants is that of the runner, which is reserved for the team’s sole non-magical athlete. Lana is insistent on being a member of the team, in part because she truly believes she’s qualified and capable, but in part because she wishes to reconnect with her Puerto Rican identity. Lana is half-white, half-Puerto Rican, and when her white American mom moves out of the island, our protagonist’s ties to the island seem severed, especially when her Puerto Rican father is abroad studying dragons.

Her wish to prove her cultural nationalism through sports is granted when Lana has a brush with death at the hands (claws?) of a dragon hidden in a wand shop, and the International Blazewrath Federation (IBF) offers her the runner position in the Puerto Rican Blazewrath Team. Lana’s mother, who throughout the introduction is mostly apathetic towards her Brown daughter, guilts Lana for desiring to compete for Puerto Rico right before severing ties with her child.

Buy the Book

Blazewrath Games

Lana’s diasporic Puerto Rican identity is constantly challenged throughout the book, especially as she joins the rest of the Puerto Rican National Team at their training center in Dubai. The biggest challenger is Victoria, a white Puerto Rican teammate from the town of Loíza, whose tragic backstory doesn’t prevent her from antagonizing Lana. Due to Victoria’s testing, and the machinations of the IBF, Lana’s desire to compete for Puerto Rico shifts. Lana’s participation isn’t a performance of nation, but of identity as she tries to prove she’s good enough to be a part of the team.

I couldn’t help but draw comparisons between Lana/Victoria and the differing views Puerto Ricans have of Gigi Fernández/Mónica Puig. For those who aren’t fans of Puerto Rican sports history, Gigi Fernández was the first Puerto Rican tennis player to win an Olympic Gold Medal competing for the United States. In 2016, Mónica Puig won the first Olympic Gold Medal in tennis for Team Puerto Rico. As Fernández defended her place as the first Boricua Olympic Gold Medalist, the media and Puerto Rican islanders debated whether it really deserved merit as she didn’t do it for Puerto Rico. This type of discourse is one often seen when talking about Puerto Rico and its position under the United States’ colonial rule, and it’s never more prevalent as it is on a world stage. In friendly, international competition, Puerto Ricans are allowed space to express their national identity without being under the United States’ shadow.

In Ortiz’s fantasy, the politics of United States’ colonialism is only made explicit once, as Lana says that all she needed to compete “was a team from [her] place of birth to be eligible for tryouts,” thus implying that any Puerto Rican born in the archipelago couldn’t be a part of the US Blazewrath team. By omitting the colonial status of Puerto Rico, while making a conscious effort to separate the US from Puerto Rico, Ortiz skirts around it and simplifies the issue of Puerto Rican identity as that of diasporic Puerto Ricans vs Puerto Rican islanders. Lana has to prove she’s Puerto Rican and not an interloper intent on “colonizing” the team full of Puerto Rican islanders.

All of this exploration is dropped when the characters find out about the main conspiracy, which was disappointing, but I guess a Fantasy book must have Fantasy stakes and not revolve around discourse of Puerto Rico’s relationship to international sports events. For that, I’ll have to resort to the academic papers that are sure to pop up after the publication of Blazewrath Games.

In a team of fifteen, often the amount of characters in a single scene made it difficult to follow distinct personalities. There are six human members, a coach, his son, and Lana, all introduced in one go. I include the six dragons, which are an endemic species called Sol de Noche that popped up suddenly across the island—because if the world thought there wouldn’t be a Puerto Rican everywhere, even as a dragon species, they were wrong. The sudden introduction of all these characters made it feel very much like I’d been invited to a distant family member’s party and my grandma was asking: “You remember Fulano, right? Go say hi to him!” Though overwhelming, the addition of fifteen other Blazewrath teams, plus all the bureaucrats involved with the plot complicated my experience. I would’ve liked to have a glossary of all characters and their respective mounts or affiliations, much like the ones found in the back of popular fantasy books.

On the other hand, Ortiz’s vast worldbuilding is aided by excerpts from fictional sources that preface each chapter help in allowing the reader entry into the world. At times the book feels cramped with how much exposition the characters have to do in setting up the major players and conspiracies. However, all the conversations pay off by the end, especially once the action around the actual games gets going.

The book is sure to make a splash, especially with those who’ve been looking to repurpose their purchased wands. Not only are there canonical queer Puerto Ricans, but there are trans characters, and Puerto Ricans who don’t speak English (talk to me about my love for Edwin and his refusal to speak anything other than Spanish). Lana’s best friend, Samira, is a literal magical Black girl who’s essential to the development of the plot. However, I would’ve still liked to see more development of the queer Puerto Rican team members, or at least for them to have taken up more space on the page.

As the main action begins, the story picks up its pace, almost as if we’re mounted on a Sol de Noche and flying at break-neck speed. Reading the rules of Blazewrath from Lana’s perspective was very different to when Lana’s playing the game, paralleling Lana’s relationship to the sport.

Even though the ending ties many of the remaining plot holes in a convenient and neat bow, Ortiz leaves us with enough hints and mysteries to unravel in the upcoming sequel. Whether Ortiz will be bringing the action to Puerto Rico remains to be seen. Either way, I imagine it will bring about more conversations, intense plots, and, of course, more dragons.

Blazewrath Games is available from Page Street Kids.

Adriana M. Martínez Figueroa (@boricuareads on social media) is a bisexual Puerto Rican writer. She holds a B.A. from Iowa State University in Women and Gender Studies with a minor in US Latinx Studies. Her words can be found on her WordPress blog (Boricua Reads) as well as inQluded and the forthcoming anthology Boricua en la Luna.